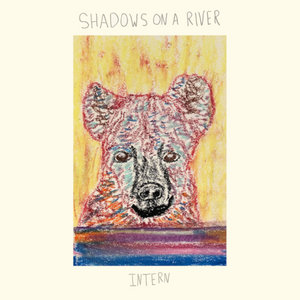

Intern by Shadows on a River

When I wrote the songs that became our new album, Intern, in 2021, I was living in Lincoln, Nebraska struggling to finish a PhD in Fiction Writing while simultaneously learning how to be a father during a pandemic. After taking a break from making music, I’d stumbled into grad school mostly because I wanted to write novels and hang around with other writers, but I’d become disillusioned both by academia and the way the contemporary publishing industry appeared to function. I’d always gravitated toward storytelling as a way to undo the rigid rules and structures of life, but professionalizing as a novelist seemed to force everyone back into even more rigid roles, our primary means of expression pigeonholed and shaved down to bullet points meant to please a fickle industry that didn’t trust its own readers. Ambiguity became a sign of weakness instead of an acknowledgment of what approaching the bigger mysteries of life had always felt like to me.

I’d been recording music and releasing albums since my early teens, quietly and tragically burning out energetically and emotionally after putting out a big ‘polished’ full band album when I turned 30–2014’s Shadows on a River album, Captured Ghosts–a record which took years of tinkering in my basement as I tried to handle songwriting, recording, mixing and production duties mostly on my own (with the help of longtime bandmates scattered around Illinois). I’d released a couple of quiet acoustic and demo albums since that time, but mostly without fanfare, sending them into the quiet dark waters that await the unpublicized internet release.

Studying novels and theory in grad school, my new obsession became the way that narratives and perspectives ruled our lives, usually to our unacknowledged detriment. Between teaching and endless schoolwork, I’d somehow begun listening to hours of old Ram Dass lectures every day, for months on end. Ram Dass–the Harvard academic and psychiatrist who took psychedelics and realized that what he’d taken for granted as his own identity and problems had merely been a set of stories he’d been telling himself without realizing–further pushed me to question the way that funneling experience and feelings into language could be disempowering and potentially dangerous, depending on how it was approached. Just as Ram Dass walked away from Harvard to become a kind of mystic, I began to question my own role in academia, desiring to throw off my own former identities like a cheap suit. All the tension in my body, the bracing against everyday life, felt tied to the stories I told myself about who I was, who I was supposed to be, and who I would never be. Words and concepts started to feel like the enemy, but words and concepts were supposed to be my bread and butter as a writer and academic.

I was still working on novels and short stories consistently, but I hadn’t written any songs in some time. I’m not sure why the inspiration struck. It’s quite possible that I saw one of my many talented friends producing something new and amazing simply for its own sake and wanted to do something outside of the classroom, outside the world of words on paper. Regardless, I wrote the nine songs that became this album in less than three weeks, immediately recording demos on my iPhone 10 as soon as I’d written down the last word of lyrics. They’d all come quickly, without thinking, without any concern about how to line up the words to produce specific concepts. Something else in me was at the wheel, as it was the other glorious times when some kind of creative work came seemingly without effort. I didn’t question it.

I’d walk the dog around the neighborhood and listen to my demos on headphones, enjoying the feeling of being part of some kind of creative expression that didn’t exactly feel like it had come from me. It felt free from my identity but also like an expression of what it meant to be alive, or something less cheesy than that. Eventually I posted snippets of the songs online with what I considered to be vibey, peaceful video, mostly of trees swaying and car headlights slowly moving through the sleepy neighborhood where I lived, just a mile or so from downtown.

Shortly after I posted a few of those clips of the demos, Danny Hynds emailed me from Japan to ask if I wanted to do something with the songs. Danny and I had been playing music together on and off since 2003 when we both attended a small liberal arts school in central Illinois. Danny has always been a mysterious creature to me. After the first performance with my undergrad band, The Infinity Room, Danny pulled the drummer aside and asked if he could join. For some reason he owned an Ondes Martenot, the strange string-controlled keyboard made famous by Jonny Greenwood on the Kid-A and beyond Radiohead albums. Danny was a tuba major who chain-smoked cigarettes and ordered keyboards from France. He was of course immediately welcomed into the band.

It was clear right off the bat that Danny was not only some kind of musical genius but also just a genuinely sweet and authentic person, both things I felt incapable of being or becoming, especially as an insecure 19-year-old. All Danny seemed to care about was music and movies and video games, but he never seemed to express genuine jealousy or resentment in the ways I often did. He was as pure as they come, as far as I could tell.

After our college band broke up, we continued to make music together, mostly as Shadows on a River, until 2014. That was when I left Illinois to go to Nebraska, and eventually Danny made his way to Japan to pursue a PhD in Media Design. I’d periodically get updates from him about the experimental dance concerts he was scoring, the video games for which he was writing stories and composing the music, and eventually the biofeedback medical devices he was using to employ human emotions in creating experimental live and recorded music. From my perspective, he seemed to have steered his passion and talents into the most sci-fi and fascinating avenues he could take them.

I pretty much immediately said yes when Danny asked to collaborate again. I didn’t have the means or energy to do anything else with these demos, having sold most of my instruments and recording gear when I left Illinois, but I knew he could at least polish them up in some way. After a few months, he sent me a couple songs that embellished the voice and guitar demos with vintage synths and the kinds of otherworldly instruments I couldn’t quite name just from hearing them on the recording. But we stalled after that, limited by the form. The voice and guitar from my demos were recorded on a single track, so there was little wiggle room to experiment in the ways that interested us. The project lingered while life and grad school threw a hefty amount of complications at us both.

And then one day a few years later, we got back to it. We had a conversation about how to take these songs that could have found themselves on a Seven Swans-era Sufjan album and imbue them with the depth and mystery that we found on more ambient and vibey albums like Burial’s Antidawn and Frank Ocean’s Endless. I’d mostly been listening to ambient music for the past few years, again trying to avoid any sense of narrative or perspective even in music, and Danny had been pushing music composition to untold limits on his own. We both looked up to visionaries like Bjork and David Lynch, and ‘feel’ was just as important to us as any other aspect of art and music. Something clicked in Danny when he found a way to digitally separate the vocals from the old beat-up classical guitar I’d used to record the demos. He ran the separated vocals through various tape machines in his lab in Japan, which seemed to breathe new life into the process. And so he began again, producing new versions of the songs at a phenomenal rate, some with over 250 tracks that somehow cohere and still leave space for the original spark of more ‘traditional’ songwriting at the heart of the recording.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I felt more seen and taken care of than I ever had musically, and all I’d had to do was give up my control and my expectations to my longtime, pure-hearted friend. As we intuitively put the album into an order and solidified the ambient segues between songs, it began to feel as though a dream I’d long forgotten was being coaxed out of the ether. I reminded myself not to push or expect or turn any of it into a concept, and something fully satisfying emerged with grace and ease. When the album was nearly finished in May, Danny took an unexpected break as his first child was born much earlier than expected. He handled that in a way I admired, too, and somehow managed to put the finishing touches on the album after some time away from the project.

I’m so grateful for my friend and his devotion to making unique and beautiful projects (he’s got so many, the list is nearly endless). I don’t know what I’ve done to be able to release another new album like this into the world, something that feels so much like me even though so much of it is Danny (and the two other brilliant musicians he recruited to add to the gentle cacophony of sounds on these tracks). These songs, from what I can tell, are about ways to see through illusions, and how to re-tell stories in a way that might free us from them rather than bind us to the old ways of being. But I’m sure, as I keep listening to my own voice singing back to me, that I’ll learn something new again from that part of me that sings out of the unending abyss inside me in those few and far-between moments when I finally step back and let it.

Tracklist

| 1. | Observation Deck | 3:43 |

| 2. | New Sun | 5:35 |

| 3. | Intern | 5:51 |

| 4. | Crash and Burn | 8:04 |

| 5. | Curtains | 6:12 |

| 6. | Cusp of Life | 9:26 |

| 7. | Give and Take | 9:18 |

| 8. | Out of Hand | 5:00 |

| 9. | Stealing a Purse | 4:46 |

Credits

David Henson: vocals, guitar, whistling

Danny Hynds: synthesizers, eurorack system, Ondes Martenot, drum machines, percussion, tape loops, field recordings

Juling Li: vocals (1, 6, 8, 9)

Mingyang Xu: saxophones (1, 2, 6, 8, 9)

Songs by David Henson

Production, Mixing and Mastering by Danny Hynds

Artwork by David Henson

Design layout by Joe Murphy

Recorded in Lincoln, Nebraska, Royersford, Pennsylvania, Ibaraki, Japan, and Yokohama, Japan.

Special thanks to our families and friends (and you, the listener).